Bedbugs: not dead yet

Bedbug infestations are on the rise in Chicago—and the number of complaints barely scratches the surface

By: Julia Thiel – Chicago Reader

Taina Rodriguez was at the dog beach with her husband and two mini schnauzers one afternoon last June when she got a disturbing phone call from her neighbor. There’s been an explosion in your apartment, the neighbor said. You should hurry home.

As Rodriguez and her husband, Hernan Velarde, both 31, made their way back to their Albany Park two-flat, other neighbors and her landlord were calling too. By the time they got there, the fire had been put out and their street and two others were blocked off by fire trucks and police. The landlord asked her not to talk to the officers, saying he’d handle everything, Rodriguez says. She didn’t argue: “I was in a complete state of shock.”

The cause of the fire, according to Rodriguez: bedbugs.

In late April, Rodriguez had started waking up with itchy welts on the right side of her body. After identifying bedbugs as the cause, she called a pest control company out to her place for a quote. They told her it would cost around $1,200 and they’d need permission from her landlord, Greg Puchalski, to do the treatment. But Rodriguez claims that Puchalski refused—even though she said she’d pay for it. “He goes, ‘No, Taina, I fix it, I fix it,'” she says. “‘I’ll do it my way.'” (Puchalski denies that the conversation took place.)

Puchalski’s fix, according to Rodriguez, was to gas the place. “He came in and put propane tanks in our apartment,” she says. “He thought he could heat up the apartment and the bedbugs would die. One of his brothers, who was also co-owner of our apartment building, had seen a segment about bedbugs on TV.”

Rodriguez says Puchalski had been using propane tanks in her bedroom to treat the bedbugs for a couple months—often when she and her husband were home—before the explosion occurred. The day of the fire, she and Velarde had been out of the house in the morning; when they stopped at home to pick up the dogs and take them to the beach, she noticed that their bedroom door was closed. Neighbors saw the explosion in their bedroom, and one claims to have seen Puchalski go in after the fire to remove the tank, according to Rodriguez.

Puchalski says he never used propane tanks in the apartment. When I called he told me that his brother Jack was Rodriguez’s landlord and I should talk to him, but eventually admitted that he was usually the one Rodriguez would call when she was having problems with her apartment. (Jack Puchalski never returned my calls.) Greg at first avoided my questions, but finally said that Rodriguez “probably” had called him about a bedbug problem, and “probably I sprayed.” He was adamant that he had never put propane tanks in the apartment, though, and said that the fire was caused not by an explosion but by an electrical problem.

Rodriguez argues that their bathroom fixtures—sink, toilet, bathtub—ended up on the second floor of her building as a result of the explosion. She doesn’t think that would happen from an electrical fire.

Greg Puchalski’s insurance company is currently investigating the case, but Rodriguez says it’s complicated by the fact that many of the neighbors who saw what happened live in buildings owned by the Puchalskis. “The community where I lived, it’s all undocumented folks. They don’t want to talk because they don’t want to get in trouble,” she says. “My brother-in-law doesn’t even want to talk because he feels that he will lose his apartment.” (Rodriguez is a U.S. citizen; her husband is not.)

Rodriguez says the fire destroyed 95 percent of their possessions, including her wheelchair and medications (she and her husband are both disabled: she has Marfan syndrome; he suffered a work-related injury that left his lower back fused). The Red Cross helped them replace their medications, and they were able to stay with Velarde’s brother, who lived across the street, while they looked for a new place. Rodriguez went back to work after taking a couple days off—she’s a constituent advocate for Congresswoman Jan Schakowsky—and Velarde went back to repairing home appliances (he’s self-employed). They found another place to live and moved in. Looking back on the incident, Rodriguez says: “Let me put it to you this way: [the bedbugs] all burned.”

Bedbugs have been feeding on humans since we first lived in caves, and humans have been going to extremes to get rid of them for just about as long. In 1777 The Compleat Vermin-Killer advised people to fill cracks in the bed with gunpowder and light it on fire; another remedy, recommended by Good Housekeeping in 1889, was composed of a mix of alcohol, turpentine, and highly toxic mercury chloride. Fumigation was also popular, first with brimstone (sulfur) and then in the 1900s with the toxic gas hydrogen cyanide.

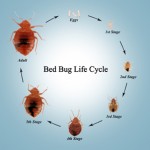

It’s easy to see why bedbugs can inspire such extreme reactions: the apple-seed-sized bloodsuckers feed on humans at night, usually leaving red, itchy welts behind (about a third of the population has no reaction to bedbug bites). They reproduce quickly, like to hide in small crevices, and can live up to a year between feedings, which makes them very difficult to eradicate. They also travel well: the bugs can crawl through cracks in the walls to an adjacent unit in an apartment building, stow away on used bedding or clothing, or climb onto a bag or coat set down in an infested area.

Home remedies notwithstanding, bedbugs flourished in the U.S. up until the 1940s. The introduction of DDT and other pesticides in the ’40s eliminated them almost entirely, and they remained extremely rare for about another 50 years, when reports of them started to multiply exponentially. The 2011 Bugs Without Borders Survey by the National Pest Management Association and the University of Kentucky, which polled close to 1,000 pest control companies, found that 99 percent of them had encountered bedbug infestations in the past year, up from 11 percent ten years ago. No one knows for sure what has caused the uptick, though leading theories include an increase in international travel (bedbugs are more common in developing countries than developed ones), the banning of DDT, and genetic mutations in bedbugs that have made them resistant to insecticides.

Few laymen know how to handle an infestation. Most bug bombs and foggers, for example, are not only ineffective against bedbugs but can spread the problem by driving bedbugs into other rooms. Dini Miller, an associate professor at Virginia Tech and one of the few researchers in the country who specializes in bedbugs, says she once talked to a guy who had set off ten bug bombs in his apartment, and when that didn’t work, he followed up with 30 more. “I’m surprised he did not blow his windows out,” she says. “The walls were so sticky with the residue, and yet live bedbugs that had fed the night before are crawling around while we’re standing there talking.”

Getting funding for bedbug research is difficult, though, because bedbugs aren’t known to carry any diseases and most funding agencies are interested in disease vectors. Additionally, Miller says, there aren’t likely to be any new insecticides on the market soon: the approval process takes about ten years. “It could not be better for bedbugs in the United States,” Miller says.

There’s very little official tracking of bedbug complaints in Chicago, which makes it difficult to get a sense of just how big the problem is locally. A list released last year by Terminix, a large pest-control company, declares Chicago the fourth most bedbug-infested city in the U.S.,behind New York, Cincinnati, and Detroit; another company, Orkin, says it’s the second most infested city, behind only Cincinnati. But neither company revealed the data behind its claims, and both are for-profit organizations that may do more business in some cities than others.

Neither the Cook County nor the Chicago health departments keep records of bedbug complaints; both agencies say it’s because bedbugs don’t spread disease and therefore aren’t considered a public health threat. The Illinois Department of Public Health doesn’t keep up with them either, but Curt Colwell, an entomologist who fields bedbug-related complaints to the department, has been unofficially tracking the number of calls he’s gotten for the past eight years. “I have seen the number of bedbug calls trending upward and relatively unchecked through 2011,” he says. Before 2004 he had no complaints of bedbugs. He got two calls that year, four the next, and ten the year after that; the number has more or less doubled each year through 2010. In 2011 he got 253 complaints, about a third of his total calls. That includes all of Illinois, though Colwell says that Chicago accounts for the majority of his calls.

The City of Chicago’s Department of Buildings tracks the number of bedbug infestations reported through 311 calls, and reports a trend similar to the one Colwell has seen. The department started keeping a record in 2006; there were 25 calls that year, 50 the next, and 103 in 2008. Since then the number of calls has increased by roughly 100 each year, totaling 376 in 2011. But that only includes the people who already suspect they have bedbugs when they call, says department spokesperson Caroline Weisser. Calls are tracked by keyword, so if someone says that they’re having an insect problem it won’t be recorded as a bedbug call, even if the city later determines that bedbugs were the issue. And, of course, not everyone who has bedbugs calls the city. The stigma associated with bedbugs means that homeowners are likely to get them exterminated quietly rather than reporting it to anyone. Even renters can be reluctant to come forward.

The Metropolitan Tenants Organization started keeping track of bedbug cases in 2009, when it got 215 calls about them; in 2010 they got 307 calls, and 372 in 2011. Those numbers are similar to the ones reported by Chicago’s buildings department, but Sara Mathers, who investigates bedbug complaints for the MTO, believes they’re artificially low.

“People are nervous about it, or they don’t know exactly what they have,” Mathers says. Or they’re afraid of being evicted, which isn’t legal but happens anyway. “So when you’re looking at the percentage of what is reported to 311 and us, it’s a small percentage.”

Mathers says infestations are often isolated—just one unit in a building with dozens or hundreds units, for example—but left untreated, bedbugs multiply quickly and can spread to other units.

She also says bed bugs are more widespread than people think: “I would venture to say that basically every single high-rise in the city is infested. Eighty to 100 percent have at least one case of bedbugs.”

Brittany Barton, 25, was living in a 60-unit building in Edgewater last August when she realized she had bedbugs. She reported it to her management company, and they sent an exterminator to spray her apartment. Barton also threw out her bed and most of her other furniture, along with some of her clothes. About a month later, she noticed more bedbugs, and the exterminators sprayed again. She wrote letters to the other tenants in her building to find out if they were having problems, and the man who lived below her immediately came upstairs to say he had them too but had been too embarrassed to say anything. They suspected but never confirmed that the bugs were coming up from two units below Barton’s, where a hoarder who collected used furniture lived. Barton says the management was trying to get the woman evicted, but in the meantime, no matter how many times her own apartment was sprayed the bedbugs came back.

This went on for three or four months, until finally Barton decided she had to get out because it was affecting her graduate studies at Loyola. “I couldn’t sleep. I started having really bad anxiety, and I felt like I was becoming obsessive-compulsive because I would walk around my apartment with a pair of tweezers and pick up every single bedbug that I found. And then I started walking in my hallway area, up and down my steps, looking for bedbugs. It took over my life.”

Barton went to her management company and asked to be let out of her lease, which they eventually agreed to—though a manager also told her, “You can leave your apartment, but anywhere you go, you’re going to bring the infestation with you.” Barton says she was very careful when she moved and hasn’t had any problems in her new place.

If residents are hesitant to report bedbug infestations, sometimes it’s with good reason. Rosine Mensah, a 72-year-old retired substance abuse counselor, first heard about bedbugs in her building in early 2009. She lives in the Beth Ann Residences, Section 8 subsidized housing for seniors in Austin. “When I first found out about it,” Mensah says, “there was a lady standing downstairs by the security office, and she was crying because they had thrown out her furniture. It was gorgeous furniture, beautiful! And they had put it out in the Dumpsters. That was before they learned anything themselves about the bedbugs.”

Mensah had never heard of bedbugs before either, but did some online research and read that discarding furniture was unnecessary. “We had people sleeping in wheelchairs, sleeping on the floor. They threw out everything. The beds, the couches, the chairs. They didn’t really have the right to throw our furniture out. They didn’t ask; they just demanded that we throw it out.”

With the help of the MTO, Mensah and a few other residents were able to organize and get the management to implement better practices for eradicating the bedbugs, like investing in a heat treatment machine (bedbugs can’t survive temperatures above 113 degrees Fahrenheit). In addition, they worked with the Department of Housing and Urban Development, which manages Section 8 programs, to get funds to replace the furniture that had been thrown away.

The bedbugs haven’t been eradicated from the building completely, though. Mensah herself got them last year (she thinks that workers who were winterizing the building tracked them in from an infested unit). Her extermination process went pretty smoothly, but there are others in the building who still won’t report bedbugs when they’re having a problem. “They will not tell anyone until they are just crawling all over the walls everywhere,” Mensah says. “They’re afraid that they’re going to throw their stuff out, or they’re embarrassed, or they’re afraid they’re going to have to move.”

Mathers says that as bad as conditions were in Mensah’s building, they’ve improved significantly in the last couple years. In some ways, things are easier now for tenants in subsidized housing than in market-rate buildings because HUD has a list of best practices and can hold management companies accountable. “We did see a lot [of bedbugs] in low-income areas, subsidized buildings,” Mathers says. “Now we’re getting more of the market rate. I’m getting a lot of calls for two-flats and three-flats and that’s what scares me. That’s where I see the problem growing.”

Ann Hinterman, housing specialist for 49th Ward alderman Joe Moore, deals with the bedbug calls that come to Moore’s office. “One of the challenges is that although there are ordinances in the municipal code that tell landlords and tenants how pest infestations need to be handled, they aren’t specific to bedbugs,” she says. Landlords are required to exterminate if two or more units of a multiunit building are infested, or if the infestation of a single unit is due to landlord negligence. Getting landlords to follow through and pay for the extermination, though, is a different matter.

Robert Shumate, 29, who works in management at a hotel downtown and lives in a 176-unit building at Sheridan and Foster, realized he had bedbugs last July when he kept getting bitten. “When I discovered I had them, I went crazy,” he says. He went to Google to find all the information he could, then reported the problem to his building’s management company. He was told that they’d call an exterminator, and also that they wouldn’t pay for it. “I was like, whatever, I need for them to be gone,” Shumate says.

The exterminator came out and sprayed, then sprayed again a month later after Shumate started getting bitten again. Meanwhile, he had been in touch with his alderman, the MTO, and the City of Chicago, and learned that paying for the exterminator shouldn’t be his responsibility since his unit wasn’t the only one in the building affected: a neighbor told him that there were several other units that had bedbugs. The management company, however, said otherwise, claiming Shumate’s infestation was an isolated one and blaming him for the bedbugs because he worked in a hotel.

“The exterminator himself, because I asked him, said you couldn’t tell,” Shumate says. “It could have been a clothing store, it could have been a theater. Maybe they came in on your maintenance man who did maintenance in an infested unit and then brought them to my unit. They don’t carry passports with them; they don’t have little GPSes.”

Since the second treatment, Shumate says, he’s been bedbug free, but he’s still battling the management company over who will foot the $300 bill. He says it’s not so much the money at this point as the principle. He doesn’t think he should have to pay for it, and says that knuckling under will just make it worse for others. “There’s a lot of shame in it. You think, oh my god, bedbugs, that’s disgusting. And it is. I’m sleeping with bugs, and they’re eating me while I’m sleeping! I think there’s a big taboo with it, and by not talking about it, it just perpetuates the problem.”

Mathers would like to see stronger legislation around bedbugs, stating that it’s a landlord’s responsibility to pay for extermination—with specific consequences if a landlord doesn’t follow through. In fact, most states don’t have laws specific to bedbugs, especially ones that dictate what a landlord’s responsibilities are. Both New York and Maine have passed bedbug legislation in the last couple years, and Florida and Texas mention bedbugs in their pest control laws—but that’s about it. Illinois, in fact, does mention bedbugs in one law, but it’s not exactly recent: it requires railroad cars to be bedbug free.

48th Ward alderman Harry Osterman is working on bedbug legislation that he plans to present to the City Council within the next few months. His office is in the process of coming up with a list of best practices, using cities like New York as a model. He’d like to see better coordination between the buildings and health departments, more public education, and a defined system of landlord/tenant responsibilities. “Chicago has a huge bedbug issue,” Osterman says. “I think the magnitude of it isn’t something people have quite come to grips with yet. Unless we’re able to deal with it, it’s going to continue to be a problem.”

Currently when a Chicago resident calls 311, an inspector is sent out to the building and if bedbugs are found, the owner is given a citation and ordered to appear in administrative court, says buildings department spokeswoman Weisser. The court works with the owner to bring him or her into compliance, and may issue fines for noncompliance. “A lot of management companies build that into their budget,” Mathers says. “Like, ‘Sure, we’re going to get a couple fines and then we’re going to keep doing what we do.'”

State laws about who pays for extermination are even less clear, says Colwell. Last year the Illinois Department of Public Health’s Structural Pest Control Advisory Council formed a bedbug subcommittee, which produced a report of recommendations to curb the bedbug problem in Illinois; the report will be presented to the legislature in the next month or so. Among the recommendations: define landlord/tenant responsibilities (tenants must report bedbugs and facilitate their removal; landlords are responsible for getting them exterminated), improve public awareness, and enable local health departments to respond to bedbug complaints.

What the legislature will do with those recommendations remains to be seen, Colwell says, but in the meantime the bedbug problem tends to be particularly severe in low-income buildings where landlords refuse to deal with the critters and tenants can’t afford to pay for professional pest control themselves.

Mathers has seen plenty of buildings that fit Colwell’s description, and says that one in Rogers Park is especially bad: some residents have been living with bedbugs for years because the landlords refuse to effectively treat the infestation. Arbie Bowman, 43, lives there with her seven-year-old daughter, Rosie, and no longer has bedbugs—no thanks to the building management, she says. After her daughter started getting bitten a little over a year ago, Bowman told the maintenance man about the problem and says that he laughed at her. “Like it was a joke,” she says. “This ain’t no joke.”

Maintenance came to her apartment a few times over the next few months to spray alcohol and put down powder to get rid of the bugs, but it didn’t help. Meanwhile, Rosie was sleeping on the coffee table because she got bitten every time she tried to sleep in her bed. “I slept in a chair, right there by my daughter watching her,” Bowman says. “I’m lucky if I got two hours of sleep at nighttime.”

Bowman started attacking the bedbugs herself, spraying the entire place with alcohol every day after her daughter left for school, even standing the mattresses on end to get all parts of them. It’s an extremely difficult way to eradicate bedbugs, which are good at hiding in tiny crevices, but she eventually managed it.

Bowman says Rosie still wakes up in the night thinking that there are bugs crawling on her. And knowing that many other units in the building are infested with bedbugs, Bowman doesn’t let anyone except her immediate family into her apartment. “I can’t take that chance,” she says. “With my daughter still having them nightmares . . . God forbid if I get them again.”

The management doesn’t tell people who are moving in that there are bedbugs and mice in the building, Bowman says, and now that they know she’s working with the Metropolitan Tenants Organization to help organize other residents, they’re trying to kick her out. Despite everything, Bowman doesn’t want to move: rent is cheap, and if she moves she’s likely to lose her job in home health care, which is in the same building where she lives.

She’s still hoping that the organizing she’s been doing with MTO will eventually make a difference. “I just want them people to get rid of the mices and get rid of the bedbugs and start helping these tenants out,” she says. “What me and my child went through for three months, I wish on nobody.”

![page-0[1]](https://www.tenants-rights.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/page-01-791x1024.jpg)

What prompted the writing of this post was a recent conversation with a tenant. The tenant was following up to report the lack of heat in her unit. She explained that not only was this problem irritating, but that her entire family has experienced constant headaches and she was even having trouble waking up, which was not normally a problem for her. She mentioned that her sister had called her earlier and she hadn’t heard the phone ring. Her kids – especially her daughter who slept in the back bedroom near the kitchen— was having a lot of difficulty waking up for school. All of these incidences are major symptoms of carbon monoxide poisoning.

What prompted the writing of this post was a recent conversation with a tenant. The tenant was following up to report the lack of heat in her unit. She explained that not only was this problem irritating, but that her entire family has experienced constant headaches and she was even having trouble waking up, which was not normally a problem for her. She mentioned that her sister had called her earlier and she hadn’t heard the phone ring. Her kids – especially her daughter who slept in the back bedroom near the kitchen— was having a lot of difficulty waking up for school. All of these incidences are major symptoms of carbon monoxide poisoning.